From Counterintelligence Operative to Family Annihilator

Almost a half-century after the terrible crime, the Deep State’s biggest murder mystery remains an unresolved cold case

Not long before Christmas, I visited a nondescript house in the Maryland suburbs of our nation’s capital, not far from where I grew up. I was in the area visiting family nearby, I had a couple free hours, so I went exploring. From the outside, 8103 Lilly Stone Drive looks like a standard 1960’s split-level suburban house, located on a quiet and pleasantly treed street in Potomac, just around the corner from the tony Congressional Country Club. The tranquil appearance betrays no hint that this residence witnessed one of the most gruesome crimes in the annals of our national capital region.

The mysterious story begins nearly five decades ago, on March 8, 1976, when neighbors grew concerned that nobody had seen the inhabitants of 8103 Lily Stone Drive in a week. Of the six people living there – a State Department official, his wife, their three children, plus his mother – there was no trace. Mail was piling up so concerned neighbors asked the local police to conduct a wellness check.

What Montgomery County Police discovered inside the empty house was something out of a gruesome horror movie. Even before they opened the front door, the cops noticed a distinct trail of dried blood, and lots of it, leading from the house to the driveway. Inside there was blood all over the house. All four bedrooms, including bedlinens and mattresses, were drenched with blood, as were several other rooms. Horrifically, police encountered not just blood but human flesh and hair. Something horrific had happened here. But there were no bodies.

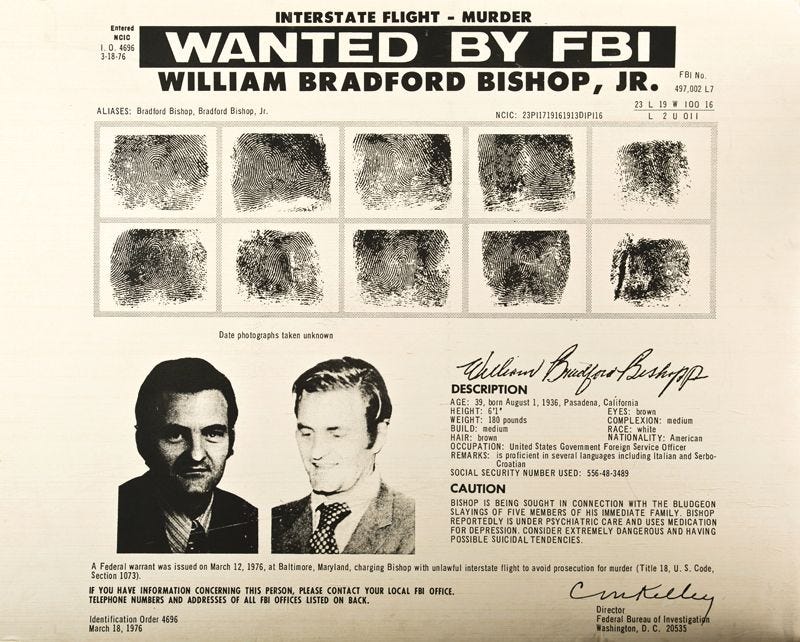

The owner of the house was 39-year-old William Bradford Bishop, Jr., a career State Department official known to all as Brad. The police wanted to talk to him, urgently, but he was nowhere to be found. Neither was his family. His wife’s VW Beetle was parked in the driveway, but the family car usually driven by Brad, a 1974 Chevrolet Malibu station wagon, was missing. Police put out an all-points bulletin for Brad Bishop and it didn’t take long for unpleasant pieces to start falling into place.

On March 2, some 300 miles southeast of Washington, DC, in a remote, swampy area outside Columbia, North Carolina, a small town on Albemarle Sound in the state’s coastal region, forest rangers got a call that there was smoke. They went to investigate and put out any unwanted blaze. The lead ranger discovered traces of a significant fire that had burned several acres of brush. He also saw a shovel and a gas can – and various body parts in a shallow pit. There were five badly burned bodies there. Since the fire was still smoldering, the forest ranger must have missed the arsonist by an hour or two, at most. The shovel was soon traced to a hardware store in Potomac, Maryland, where it had been recently purchased.

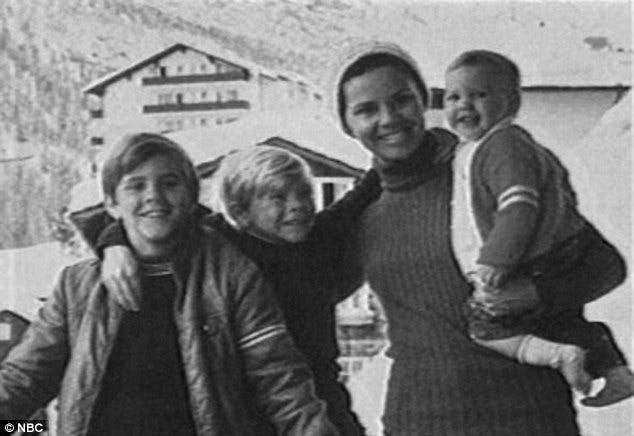

Forensic and dental analysis soon revealed that the charred bodies were the Bishop family, or most of it: 37 year-old Annette, 14-year-old Brad III (known to the family as Pino), 10-year-old Benton, 5-year-old Geoffrey, and Brad Bishop’s 68-year-old mother Lobelia. The only one missing was Brad.

Before long, detectives developed a detailed picture of what happened on March 1-2. Brad left his State Department office at Foggy Bottom late on the afternoon of Monday, March 1, as usual. Having cashed a check for $400 at his bank earlier in the day, he went shopping. At approximately 6 p.m., he purchased a gas can and a sledgehammer at a Bethesda Sears. He then filled up his station wagon at a nearby gas station. Lastly, Brad bought a shovel at a hardware store near his home.

Detectives assessed that Brad Bishop arrived at 8103 Lilly Stone Drive between 7:30 and 8:00 and proceeded to annihilate his family with brutal force. The first victim was Annette, who was downstairs reading a book. He smashed her skull with the newly purchased hammer. The next to die was Brad’s mother Lobelia, who had been out walking the family’s dog, a golden retriever named Leo. Upon her return, she too was savaged with the hammer to death. Then, Brad methodically murdered his three sons, who were upstairs, asleep in their bedrooms. They offered no resistance and died in their beds. The oldest son, Pino, was smashed with exceptional brutality, far more than was needed to kill.

The dastardly deed done, Brad wrapped the bodies of his family in blankets and towels and, under the cover of darkness, hauled them into the back of the station wagon. Taking Leo with him, Brad headed for eastern North Carolina, where the following day he burned his family in a shallow pit to hide his crime. He failed in that endeavor, but Brad Bishop successfully fled the scene of both the murders and his try at a cover-up.

The last confirmed sighting of Brad Bishop occurred on March 2, several hours after the arson, when he used his credit card to purchase a pair of tennis shoes at a sporting goods store in Jacksonville, NC, about 130 miles south of where he dumped his family’s bodies. Witnesses confirmed it was Bishop who bought the shoes, accompanied by Leo, while some said he was with a dark-skinned women who has never been identified. There his trail ran cold.

Seventeen days after the murder, on the afternoon of March 18, a National Park Service ranger found the Bishop station wagon, parked at the Elkmont Campground in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, in easternmost Tennessee, on the North Carolina border. Detectives surmised that Brad Bishop parked it there around March 5; a local had observed the Chevrolet parked there the following day. The abandoned vehicle contained a great deal of dried blood, including a blood-soaked blanket, Brad’s personal items including a shaving kit, plus dog treats. Of the wanted man and his dog there was no sign. Since the car was parked near a popular trailhead, investigators theorized that Brad and Leo joined the throng of hikers and disappeared into the vast expanse of the half-million-acre forested park.

The next day a Maryland grand jury indicted Brad Bishop on five counts of first-degree murder and related charges. Forty-eight years later, he has never appeared in court to face those charges.

High were the hopes for a break in the case in the weeks and months after the crime. To catch him they needed to understand him, thus detectives examined all aspects of Bishop’s life, since he was far from your average murderer. Well educated with an apparently successful career, Bishop seemed an unlikely family annihilator, but there was little doubt about his guilt. Who really was Brad Bishop?

Raised in Southern California by a petroleum geologist father and homemaker mother, Brad was an only child with a comfortable life. He followed his father’s footsteps to Yale University, where he was a middling student with a knack for languages. After graduating in 1959, Brad married Annette Weis and joined the U.S. Army, which assigned him to counterintelligence work and trained him in the Serbo-Croatian language (which he learned to speak well, in addition to French, Italian, and Spanish). During his four years in Army Counterintelligence, much of it spent in Italy, Brad focused on Yugoslavia, the renegade Communist regime next door. His work ranged from listening to Yugoslav radio broadcasts to attempting to recruit Yugoslavs visiting Italy to spy for the United States. Although such operations hardly made him James Bond, four years in Army Counterintelligence gifted Brad Bishop certain skills in the dark arts of espionage that would help him disappear after he murdered his family.

After leaving the Army, Brad picked up a master’s degree from Middlebury College, then he joined the State Department as a Foreign Service Officer, which seemed like an ideal job for a polyglot with ambitions. His career followed the typical pattern. In 1965, the Bishop family headed to Ethiopia for Brad’s first posting as a junior FSO. From 1968 to 1972 he was in Italy, assigned to multiple U.S. consulates there. His last overseas posting was in Botswana from 1972 to 1974. Then, in what turned out to be his last job, he was assigned to State headquarters in Foggy Bottom, as all FSOs have to do sometimes if they expect promotion, where Brad worked on international trade issues. Outwardly, his biography offered nary a clue as to why Brad Bishop decided to annihilate his whole family. He led an active lifestyle, enjoying the outdoors, staying physically fit, and picked up flying as a hobby during one of his African postings.

However, closer examination revealed hints of mounting problems in Brad Bishop’s world. Colleagues described him as high-strung, even narcissistic, with a quick temper and neat-freak tendencies, resembling what we would today term obsessive-compulsive disorder. Brad possessed plenty of self-esteem and, it seemed, disregard for following rules he didn’t care for. During his Army service, he was reprimanded for poor security practices such as failing to secure classified information and leaving classified safes unlocked, which he considered “too much bother.”

Then there was his depression. By the late 1960s, as his family grew, Brad Bishop developed insomnia. He visited a psychiatrist and began taking anti-depressant medication. His private diary revealed unhappiness and increasing disenchantment with his life trajectory – though no indications of violent tendencies. Much of Brad’s discontent centered on his career. He planned to be an ambassador by age 50, but that dream seemed to be dissipating. Brad didn’t like his desk job at Foggy Bottom and hankered for another overseas assignment, not least for financial reasons. FSOs serving overseas enjoy perks like housing and amenities paid for by the State Department, artificially inflating their salaries. Returning to work at Main State meant a lifestyle reduction, in practice.

Brad’s salary of $26,000 ($145,000 today) was decent but not lavish, considering it wasn’t cheap to live in Potomac. His mother helped out, but money was tight in the Bishop household – as it was for many families in the 1970s when, as now, inflation ran high. Annette, however, wanted to stay in the Washington area, which she enjoyed. Friends said she was disappointed in Brad’s lack of career advancement. Although the family’s finances weren’t dire, Brad was growing increasingly frustrated.

But did all of this explain mass murder? Detectives learned that when Brad Bishop left Foggy Bottom for the last time late on the afternoon of March 1, he was in a foul mood. As he walked out of the building he encountered a colleague, Roy A. Harrell, Jr., and expressed his anger. The new FSO promotion list was out, and Brad’s name wasn’t on it, as he had anticipated. Harrell tried to calm him down and suggested they meet soon to discuss career matters. Within a few hours the Bishop family was dead.

Since detectives uncovered little if any evidence of advanced planning for the terrible crime, despite extensive investigation, they deduced that, for reasons known only to himself, being passed over for promotion again triggered unfathomable rage in Brad Bishop, who decided on the spur of the moment to butcher his whole family, then disappear.

Many investigators believed that Brad Bishop took his own life somewhere in the Great Smoky Mountains, an easy place to disappear and never have your remains found. However, the wanted man’s outdoor skills convinced others that Brad was very much alive, having fled the forest and gone on the lam – but where? He was a well-known fugitive, and it would be difficult for him to travel far without getting noticed.

Yet, that’s exactly what he did. In July 1978, a Swedish woman who had met Brad Bishop in Ethiopia years before, said she saw him twice in a Stockholm public park over one week. Although she was positive that it was Brad, she failed to contact the police because she didn’t know he was wanted for murder.

More compelling was a chance encounter six months later in Sorrento, Italy, a country that Brad Bishop knew well. In a public men’s room, a State Department colleague found himself face-to-face with a bearded man whom he immediately recognized. He asked him, “Hey, you’re Brad Bishop, aren’t you?” In panic, the surprised man stated, “Oh no,” in an American accent and promptly fled the restroom. The colleague who encountered him was none other than Roy Harrell, the FSO who was the last to talk with Brad on March 1, 1976. This identification seemed ironclad.

Nevertheless, despite international police cooperation, Brad Bishop’s trail went cold, and the case stagnated. How exactly had the wanted man managed to disappear and stay that way for years? How many passports did he possess? How was he paying for his secret new life, without being detected? No answers were forthcoming, and whispers soon spread that the Brad Bishop mystery involved more than mere mass murder. Was Brad Bishop really a spy? Was his disappearance caught up in secret international intrigue?

This seems unlikely, contrary to many rumors over the decades. From all appearances, Brad Bishop was a regular State Department FSO, not an intelligence officer using State cover for his espionage activities. CIA and other Intelligence Community agencies employ State Department cover for official purposes, in varying ways – that’s all I can say about that here – but Brad doesn’t look like one of those, based on his career path. However, some intelligence affiliation cannot be ruled out entirely based on unclassified information, and there seems no doubt that his past in Army Counterintelligence prepared Brad Bishop well for life as an international fugitive.

Where did he go? Over the years, claims of sightings trickled in from no less than ten European countries, but none of them were timely or detailed enough to lead police to Brad Bishop. Although the sensational case was never forgotten in the Washington, DC, area, investigative leads gradually dried up, as they inevitably do with the march of time, and hopes of finding the State Department’s mass killer slowly faded.

Detectives never gave up, however. They encouraged journalists to keep the case in public view. Anniversaries of the murder of the Bishop family launched new reports but few fresh leads. Optimism surged when America’s Most Wanted broadcast an episode on the Bishop case in January 1991. In 1989, AMW broadcast an episode about John List, another notorious family annihilator who murdered his whole family – just like Bishop, List killed his wife, three children, and his own mother – in New Jersey in 1971 and escaped justice. Shortly after AMW profiled List he was unmasked and arrested.

Unfortunately, AMW’s episode about Brad Bishop brought some new leads but nothing tangible. The last credible sighting of Brad by someone who knew him was in Switzerland in 1994. A former neighbor who was acquainted with the Bishop family spotted Brad on a train platform in Basel, just a few feet away from her. She was confident it was the wanted man.

Montgomery County Police have never closed the Bishop case. Over the years, sightings have trickled in, as have claims that Bishop is dead. Local police and the FBI have run these down diligently, to no avail. In 2014, the FBI exhumed the body of a John Doe who was killed by a car in a hit-and-run in Alabama in 1981 whom locals claimed looked a lot like the wanted State Department killer. DNA testing revealed this, too, wasn’t Brad Bishop. Later that year, investigators caught up with an 81-year-old American fugitive in Mexico, thinking it might be Bishop. It wasn’t, rather it was Robert Anton Woodring, who was on the lam for 37 years for fraud.

There have been mysterious twists too. It eventually emerged that in the run-up to killing his family, Brad Bishop had corresponded with federal prison inmate Albert Kenneth Bankston, locked up in Marion, Illinois, via mail. Their letters were cryptic and made no mention of murder, but nobody could explain the reason for the strange correspondence in the first place. The timing was odd, leading some to speculate that Brad plotted to have his family murdered while he was in Geneva on State Department business for a week in the winter of 1976. When that didn’t happen, he did the deed himself. Since Bankston died in 1983, this was another trail that ultimately led nowhere.

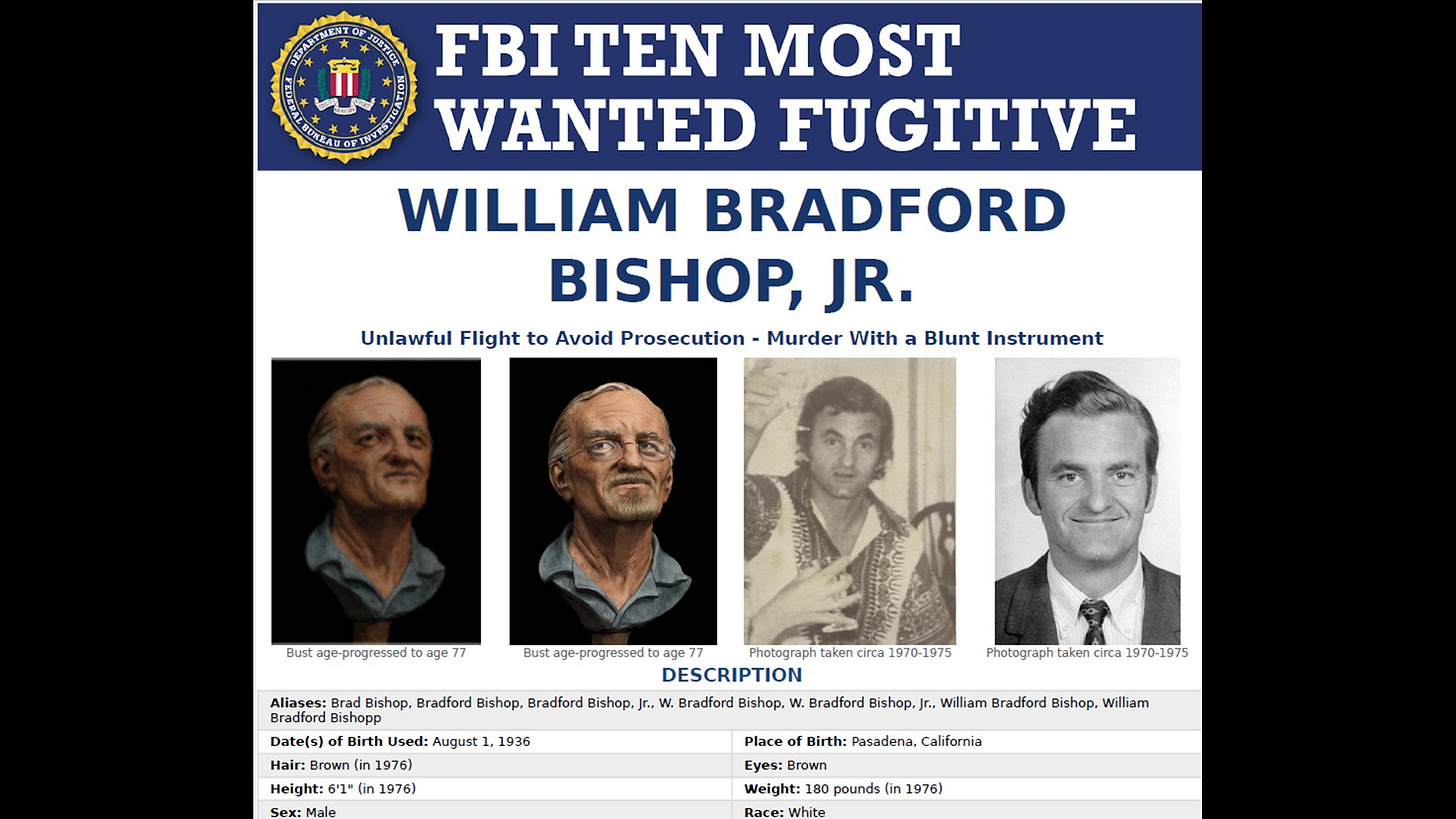

In 2014, the FBI upped the ante by placing Brad Bishop on its Ten Most Wanted list. He was the oldest fugitive and the coldest case to make that famous list. Although the Bureau added age-enhanced images to assist in finding the now-elderly fugitive, Brad remains at large. Most investigators think he started a new life – they are divided over whether that’s in Europe or perhaps he eventually returned to the United States – and he might even still be alive today

The Bishop case has always brimmed with strange happenings, and another landed in 2021 when it emerged that Brad fathered an illegitimate child when he was a student at Yale. His daughter, now a woman in her sixties, a retired North Carolina drama teacher, was born in Boston in 1957 to an unwed mother and put up for adoption. DNA testing revealed that Brad Bishop was her father.

Barring a very unlikely investigative break after almost half a century, the Deep State’s greatest murder case seems destined to remain officially open in perpetuity. If Brad Bishop is alive, he’s 87 years old. Perhaps he’s pondering a deathbed confession. Regardless, he got away with it.