Remembering Al Gray, SIGINT Warrior

The legendary 29th Commandant of the Marine Corps is being honored with his passing, but the full story of his illustrious intelligence career has never been told

The Marine Corps is in mourning today. All around the world, Marine flags are flying at half-mast to honor the passing of General Alfred M. Gray, Jr., who died yesterday at the age of 95. Even in an institution known for its colorful characters, Al – he was always Al – was one of a kind. As the official message from Headquarters, Marine Corps from the current Commandant explained, announcing the death: “He was a ‘Marine’s Marine’ – a giant who walked among us during his career and after, remaining one of the Corps’ dearest friends and advocates even into his twilight.”

Gray’s official biography is impressive enough. He was a “mustang” as they say in the naval service, a former enlisted Marine. He joined the Corps as a private in 1950, a kid from the Jersey Shore, and he rose to the rank of sergeant before receiving his commission as a second lieutenant in 1952. Gray saw extensive combat in Korea and Vietnam, receiving the Silver Star for valor in 1967 for his rescuing wounded Marines who were trapped in a minefield, under enemy fire. Gray’s career included command of infantry units up through the battalion and regimental levels, as well as overseeing the difficult evacuation of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon in April 1975.

Gray then got his stars and rose as a general officer, including command of the 2nd Marine Division. The 220 Marines of Battalion Landing Team 1/8 who were killed in the bombing of their peacekeeping barracks in Beirut on Oct. 23, 1983, came from Gray’s division. He felt their loss acutely. After his retirement from the Corps, he attended the annual remembrance service for 1/8’s sacrifice held at Jacksonville, North Carolina, to the end of his life. Gray spent time with each name engraved on the memorial wall there.

What made him famous, however, the reason even young Marines today know Al Gray’s name, was his tenure as the Corps’ 29th Commandant from 1987 to 1991. His appointment was pushed by then-Navy Secretary Jim Webb, who served as a highly decorated Marine junior officer in Vietnam.* A congenital hard-charger, Webb wanted the Corps to regain its fighting edge. He sought a warrior to lead the Marines. He got one.

The official accomplishments of Gray’s tenure as Commandant are impressive if banal sounding to civilians. Foremost among them was the promulgation of a new doctrine called Fleet Marine Force Manual 1 (FMFM-1), Warfighting. As HQMC observes of Gray’s passing, “This document, barely over 100 pages, has become legendary among military doctrine and remains the foundation for how the Marine Corps thinks about, prepares for, and executes all Marine Corps operations.” Gray inculcated Marines of all ranks in aggressive maneuver warfare, including amphibious operations. Al wanted the Corps to return to its traditional core missions, and he ensured that they did. He placed a premium on professional military education for all ranks. The proof of his concepts was demonstrated by the stellar performance of the Marine Corps in the Gulf War in early 1991, where the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions penetrated thick Iraqi defenses and liberated Kuwait with far fewer American casualties than had been predicted.

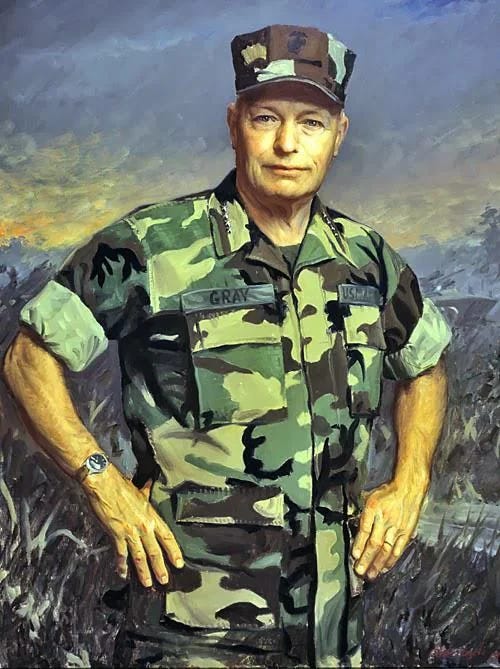

Gray rebranded the Corps in his own image, and Marines loved him for it. He was seldom seen in dress uniform. Emphasizing his warrior identity, Al was the first Commandant to have his official portrait and photograph taken in his combat utility uniform, which made him look like any other Marine, except for the stars on the collar if you looked closely enough. Enlisted Marines especially loved plain-spoken Al; they knew he understood their concerns, as he had been one of them, just a grunt. The Commandant had a gift for pithily wise aphorisms about war and leadership, which his admirers termed “Grayisms.” There were so many of these that there’s a whole book of them. The most famous of them will endure as long as there is a U.S. Marine Corps: “Every Marine is, first and foremost, a rifleman. All other conditions are secondary.”

Gray retired in 1991, after the Gulf War victory, but he remained active in numerous national security matters well into his nineties. His affection for his beloved Corps never waned. Neither did the esteem in which all Marines held Al Gray. However, there was another, secret Al Gray which even well-researched obituaries omit.

That was the spook. It’s time to explicate Al Gray’s other biography, the secret one. This was classified for decades but it can now be revealed, at least some of it. From the beginning of his commissioned career, Gray was immersed in intelligence missions. In Korea, he witnessed the value of tactical signals intelligence to support Marine operations. Here began Gray’s four-decade association with SIGINT, which happened to coincide with the 1952 birth of the National Security Agency. Marines had conducted impressive tactical SIGINT operations in the Pacific during the Second World War against Japan, but those skills had been largely lost in the postwar demobilization. In the 1950s, while still a junior officer, Gray worked to ensure that these vital, but highly classified skills gained a permanent foothold in the Corps, lest they be lost again.

This required the Marines to develop consistent standards not just for tactical SIGINT operations – the listening-in on enemy communications on the battlefield, often under fire, an arcane skill – but for all the logistics and training that underpinned such Top Secret work, including language training, communications analysis, and common security standards. Gray was an aggressive advocate for all such practices starting in the 1950s and remained so throughout his career.

Neither did Al confine his vision to tactical SIGINT in support of deployed Marines. He wanted the Corps to support national level SIGINT too, which required a close relationship with NSA. Gray worked from the mid-1950s to foster that hush-hush partnership, resulting in the establishment of what would become known as the Marine Cryptologic Support Battalion (as it remains today), which is the Marine unit supporting high-level NSA missions around the world. Gray stood up two units, one each in Europe and the Pacific, to develop this capability. He wanted the Marines to support Naval Security Group missions, which were subsets of NSA; from 1956 to 1958, Gray commanded the Marine detachment at the NSG Activity Kamiseya, Japan, as proof of the concept.

By the early 1960’s, Gray was the go-to Marine when it came to SIGINT and he took his skills to war in Vietnam, where he proved his ideas and made actionable intelligence a core component of how the Corps did battle. Marine tactical SIGINT capabilities resided in what it euphemistically termed Radio Companies (later Battalions). Then-Captain Gray stood up and commanded the 1st Radio Company in Hawaii from 1958 to 1961, establishing a standing SIGINT capability. Then, he led it to war.

Now a major, between May and August 1964, Gray commanded the Special Engineering Survey Unit in South Vietnam, which was the cover-term for a test-bed tactical SIGINT unit that was deployed near the Demilitarized Zone with North Vietnam. Gray led two other officers and 27 enlisted Marines from the 1st Radio Company on a Top Secret trial-run to see how much intelligence could be gained about the enemy by forward-deployed SIGINT collection teams. This was dangerous work in “bandit country” so Gray’s detachment had two platoons of infantry assigned as their protection. This unit became the first Marine ground unit to conduct independent operations in Vietnam. Gray’s collection teams deployed to mountaintops up to 5,500 feet high near the DMZ for weeks, dependent on helicopters for supply, always vulnerable to enemy attack. Frequently short on food and water, the teams grew weary, but they showed what could be done, collecting considerable actionable intelligence on North Vietnamese activities. Al Gray had been right.

He served in Vietnam two more times in an intelligence capacity. Around the time of the infamous Tet Offensive in early 1968, Gray commanded all Marine SIGINT units in-country, drawn from the 1st Radio Battalion. In the summer of 1969, he commanded high-level intelligence and reconnaissance for all Marine forces serving along the DMZ. By this point, the effectiveness of tactical SIGINT in the field was indisputable, and the Marines would never again allow such valuable capabilities to wither on the vine.

Indeed, today’s Marine cryptologic effort, consisting of four active SIGINT battalions (headquartered in California, North Carolina, Hawaii, and Maryland), is as much part of Al Gray’s legacy as his famous warfighting doctrine, although few people know this, including most Marines. As Commandant, Al was a robust supporter of all intelligence, especially SIGINT, and he ensured that the Top Secret techniques and skills he developed and proved in Vietnam became standard operating procedure. The details of his efforts, particularly with NSA, remain classified, but his historic intelligence legacy can now be stated publicly, at least in outline.

NSA admitted General (ret.) Al Gray to its Hall of Honor in 2008. Semper Fi, Al!

*The same Jim Webb who subsequently served as a Democratic Senator from Virginia, 2007-2013, then ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016, regrettably unsuccessfully.