Sometimes the Mystery is that there is no Mystery

What better way to ride out a hurricane than to unravel the intelligence backstory regarding what really happened to Amelia Earhart?

“Truth is stranger than fiction” is one of those aphorisms attributed to Mark Twain where the important second half is usually omitted: “because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; truth isn’t.” I can attest that, once in a while, the truth turns out to be not just stranger, but more unpalatable than fiction tries to get away with.

I was pondering Twain’s wisdom as I waited for another hurricane to land in my home state of Florida, the second hurricane in as many weeks to hit here, and Milton looked like a real doozy. I got a welcome distraction on Wednesday morning from my hurricane preparations when I received a query from an old friend in the spook trade who wanted my take on some recent-ish news in the case of Amelia Earhart.

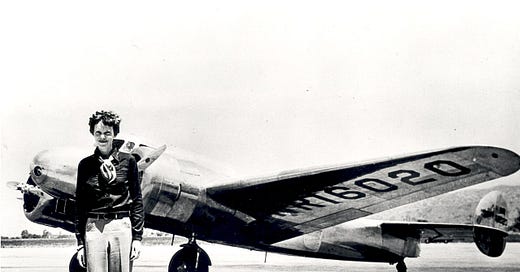

You can’t call a missing person’s case from 1937 a headline item, but fascination with the lost aviator and media star has never entirely faded, nearly nine decades after she disappeared. I’ve had a passing interest in the Earhart case for a long time. My friend came across a story from a few months ago that some rich guys financed a deep-sea expedition and claimed to have found Earhart’s missing aircraft 16,000 feet down, at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. I was pressed for time, so my reply was curt:

Amelia was an overconfident pilot who didn’t understand navigation or radio and she ran out of gas and crashed in the drink. I doubt these guys found her, but at least they’re looking in the right place.

Earhart retains a sort of cult status, particularly among the girrrrl power aviation subset, even though, in truth, she was the 1937 Darwin Award winner. Sadly, she killed not just herself, but also Fred Noonan, her navigator. While it would be unfair to term Earhart a bad pilot, her myth overplayed her skills, plus she had a persistent habit of attempting flights that pushed her abilities to the limit, and sometimes beyond. She was an unashamed fame-seeker, and her unconventional marriage to her publicist, the publishing heir George Putnam, was more about mutual promotion than companionship or fidelity. Unfortunately, Earhart’s reaching for new, ever edgier records to break eventually was going to go catastrophically wrong, and so it did in the summer of 1937.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to TOP SECRET UMBRA to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.