Ukraine is Losing the War

How Kyiv’s fall fuck-up set the stage for an even worse spring – as history seems to be repeating itself, ominously

We are less than three weeks away from the current round of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine entering its third year. Similarly, this month marks a decade since President Vladimir Putin decided to attack his neighbor and steal Crimea plus parts of Ukraine’s southeast. This is Europe’s biggest and bloodiest war since 1945 and it shows no signs of ending soon. Kremlin statements that it’s planning on battling Ukraine for several more years indicate that something like the awful 1980-88 Iran-Iraq War, a brutal attritional struggle, has reappeared.

This newsletter had quite a bit to say about the current round of the Russo-Ukrainian War, particularly as it unfolded, but since then I’ve generally stepped away from much commentary on the conflict. It’s not that I don’t have thoughts: as a military historian who has performed high-level intelligence analysis of more than one war, plus knowledge of Eastern Europe, I’ve pondered this struggle extensively. There’s simply not been any good reason to expose myself to the online opprobrium which greets anyone who looks at the Russo-Ukrainian War analytically rather than emotionally.

Not that I’ve ever hidden my biases in this conflict. I am unabashedly pro-Ukrainian and anti-Putin and have been since long before this became the only socially acceptable position in the West. I published a book in 2015 which explicitly compared Ukraine’s heroic struggle against Moscow to similar efforts by Central Europeans a century before. My people have been fighting the Moskali a long time. However, none of that matters online, particularly on Twitter (or X, or whatever the world’s richest ketamine addict is calling it this week), where any deviation from the acceptable line on Ukraine will get you vast amounts of nasty trolling. The hivemind people who embraced Black Lives Matter emojis in 2020 shifted to the Ukrainian flag two years later, while keeping their fanaticism and imperviousness to facts.

The Russo-Ukrainian War offers lessons in many things, especially regarding propaganda – which isn’t a bad word, rather a venerable and necessary weapon of war. Kyiv has excelled at propaganda more than at military operations, offering many lessons on how to win international sympathy for your cause. The Kremlin made this easy, with its repulsive conduct throughout this war. Putin’s message that Russia is battling the American-led world order in Ukraine – that country is merely the battlefield, Russia is fighting the Devil himself – may resonate in certain places, including the Global South, but it falls flat among WEIRDs, who find Russian attitudes offensively incomprehensible.

In contrast, Kyiv has done a remarkable job of winning Western sympathy for their cause. Here President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s background as a TV celebrity has paid handsome dividends (the obvious parallels with Donald Trump, who similarly parlayed TV stardom into the presidency, are impolitic to notice). His intuitive understanding of his Western audience was worth many combat brigades to Ukraine. That said, propaganda has two audiences, foreign and domestic, and it’s increasingly apparent that Zelenskyy’s messaging magic worked better on Westerners than Ukrainians. The current political drama in Kyiv, where Zelenskyy is widely believed to be on the cusp of firing Gen. Valerii Zaluzhnyi, commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces (ZSU) since 2021, indicates serious problems with civil-military relations. Zaluzhnyi seems to have gotten too popular for the president’s liking. Ukraine’s mounting difficulties with maintaining military manpower likewise hint at the war’s growing unpopularity as casualties rise and draft avoidance spreads.

In truth, Zelenskyy’s propaganda acumen abroad may have proved too effective. Presenting Ukraine’s cause in highly moralistic language, which was so potent in 2022, presents a challenge two years later. Even the Biden administration is now hinting that a diplomatic solution is required to end the battlefield stalemate, yet how can Kyiv be expected to parley with the aggressor whom it has successfully portrayed as genocidal monsters? Moreover, Zelenskyy’s constant cheerleading created expectations of battlefield victories – even total liberation of all Ukrainian territory – that simply have not emerged.

Perhaps most seriously, Ukraine’s messaging to Western audiences no longer resonates as it did in the recent past. Some of this can be attributed to the current Israeli war against HAMAS in Gaza after the Oct. 7 terrorist attacks. U.S. aid and attention are focused there now more than Ukraine. Neither was it wise for Zelenskyy to pander to the West’s beautiful people alongside the ZSU needlessly indulging in WEIRD sexual trendiness, actions which have only served to alienate more than a few Westerners, many of whom were previously pro-Ukraine.

Yet the biggest blame must fall on Ukraine’s high-volume fans in the West who have harmed Kyiv’s cause with their shrill intolerance. Their online world is a starkly binary place, filled with cartoonish playacting of good versus evil. In 2020, they allowed only two positions: Do everything that BLM wants, without question, or you’re pro-Ku Klux Klan. Since 2022, they have replicated that take with Ukraine substituting for BLM and Putin taking the place of the KKK.

This online mania has impacted Western reporting on Ukraine. Just as instant “terrorism experts” appeared in the media after 9/11 and equally neophyte “disinformation experts” came out of the woodwork around 2016, so we have been treated to much commentary on the Ukraine war by people who have no idea what they’re talking about. Moreover, nobody sensible wants to incur the online wrath of NATO doge-fellas, therefore the media has ignored necessary questions about this conflict. We have seen much reporting on alleged Russian losses of men and materiel, of varying levels of plausibility, yet very little on Kyiv’s losses, which must also be massive, given the intensity of combat in southeastern Ukraine. How can bona fide experts be expected to perform meaningful analysis of the war when there’s virtually no publicly available information about the ZSU’s actual condition? The unspoken rule governing Western media coverage has been: Kyiv’s propaganda isn’t propaganda and must not be questioned (or you love Putin).

Hence the recent news that the war isn’t going well for Kyiv has taken many in the West by unpleasant surprise, even though anyone who understands military operations could detect ominous indications mounting many months ago. The conflict has become protracted and attritional, while the Russians have wound up fighting like, well, Russians. After a rough start, with much embarrassing fumbling, Moscow has returned to its old habits of using manpower energetically, without squeamishness about casualties, bolstered by lots and lots of artillery. Similarly, Russian acumen in electronic warfare, what they call radio-electronic combat, as a force-multiplier to nullify some of the modern NATO weaponry that’s been given to Ukraine can only surprise people who know nothing about Russia and its military.

All the same, the silencing techniques of Kyiv’s Western superfans no longer seem to be working. Time is perhaps the least understood aspect of strategy-making yet is vitally important. Simply put, the large-scale financial and materiel burdens assumed by NATO countries to support Ukraine’s war effort have been politically sustainable for a couple years, but perhaps not for a half-decade or more. Putin-shaming Westerners who have questions has reached its limit, instead becoming counterproductive. After the astonishing debacle of our losing, two-decade war in Afghanistan, which witnessed the theft of billions of U.S. aid dollars by our local partners, it’s understandable to ask how much aid has gone astray in Ukraine, since that country has an intractable corruption problem to rival Russia’s own. Similarly, that normal Americans are wondering why many politicians in Washington seem more interested in securing Ukraine’s borders than America’s, in the middle of the biggest migration crisis in our history, isn’t proof that Republicans love Putin but that they loathe Joe Biden.

Primat der Innenpolitik is a German phrase which explains why Congress has lost interest in helping Ukraine, as it’s become yet another partisan football in our ugly domestic cold civil war. This couldn’t be happening at a worse time for Kyiv, which is running out of men, weapons, and munitions, while the Pentagon’s aid pipeline has run dry. Fantasies of quick victories or regaining Crimea have faded, supplanted by the harsh reality that the war is now attritional and, just as God supposedly is on the side of the big battalions, Russia’s much greater manpower and military-industrial resources indicate that Ukraine will have a difficult time winning this war – and cannot without massive amounts of NATO assistance.

Online cope is fading too. Ukraine’s helpers abroad consistently have pushed myriad NATO Wunderwaffen in a downright Hitlerian manner as the salve to the ZSU’s shortcomings in men and munitions. First it was tanks like Leopard 2s and the M1 Abrams, then it was HIMARS rocket artillery, now it’s F-16 fighters: these will turn the tide, at last. Nobody can discount the impact of weapons on the battlefield, technology matters, yet these systems will no more win the war for Kyiv than V-1 and V-2 rockets, Me-262 jet fighters, and Tiger II super-tanks won World War Two for the Nazis. The unavoidable truth is that, on its current trajectory, Russia is tracking to win this war, though perhaps no time soon, and at terrible cost. Only enormous amounts of NATO military assistance, which seem to be beyond the capabilities of the West’s mostly dilapidated defense industries, can change that reality now.

Instead, Ukraine is now losing. The winter has halted major military operations, while the front sees daily artillery duels in the southeast that the shell-starved ZSU is losing, but few large-scale attacks. Both armies are tired, badly bloodied, and hunkered down for the winter, licking wounds while waiting for the spring thaw and the mud to disappear. Few doubt that the spring will bring a major Russian offensive, somewhere, that Ukraine appears poorly positioned to defeat. That offensive may determine the war’s outcome. Therefore, it’s important to review recent military operations in Ukraine, to assess what may happen this year.

Ukraine has enjoyed two unambiguous successes in this war: the crafty defense of Kyiv at the outset, against a bumbling Russian effort at a coup de main which failed disastrously; and the September 2022 offensive around Kharkiv, which inflicted a significant local defeat on Russian forces. Both were the handiwork of Gen. Oleksandr Syrskyi, the commander of ZSU Ground Forces. However, Kyiv oversold the success of the Kharkiv operation both at home and abroad. ZSU forces punished thinly spread, mostly second-rate Russian units there.

The following spring, Kyiv got ready to launch its misnamed strategic counteroffensive* in the southeast, yet it was delayed until June. The propaganda hype surrounding this operation was impossible to miss. Expectations were high and the offensive, which was projected to achieve successes like Croatia’s historic Operation STORM in August 1995, was led by Ukraine’s NATO (mostly U.S.) trained and equipped brigades, the ZSU’s version of shock troops.

However, Kyiv’s usual propaganda magic didn’t help this time: Ukrainian officials were cagey about when the offensive even started and its wasn’t until mid-summer that it became evident that a major operation was in fact underway. Although Kyiv’s Western cheerleaders did their best to sell the offensive, it quickly got bogged down in bloody attritional slugfests along the extended southeastern front. The simple truth is that the ZSU never enjoyed significant overmatches in men or firepower against the Russians, as they needed to if they expected to achieve strategic success. To make matters worse, Ukrainian forces undertook a series of disjointed local attacks, failing to concentrate their forces in any one place, what experts call the Schwerpunkt.

By the onset of fall, as casualties mounted, even Kyiv’s superfans were beginning to allow that the “counteroffensive” wasn’t proceeding as promised. Combat engineering has long been a Russian specialty, and attacking into dense defenses against dug-in defenders who are protected by belts of minefields and battalions of pre-sighted artillery is among the most difficult of military undertakings, thus nowhere along the southeastern front did ZSU attacks make any gains which could be termed more than minor. All you needed to know about how this operation would proceed could be derived from the Wikipedia entry on the mid-1943 battle of Kursk, where the Wehrmacht attacked right into dense Soviet defenses without any superiority in men, tanks, artillery, or airpower.

None can fault Ukrainian soldiers for any lack of bravery, but heroism can’t substitute for competence – or weight of shell. As casualties mounted and unit commanders fell, ZSU tactical leadership suffered and, contrary to NATO claims, ZSU high-level leadership still displayed some bad old Soviet habits (as of course the Russians do too). The fighting quickly devolved into sharp platoon-level skirmishes lacking any strategic import or even rationale. Still, Kyiv kept the “counteroffensive” going long after it lost any military logic and no breakthrough ever emerged.

The whole operation was more a political than a military act. Kyiv wanted to demonstrate that, bolstered by NATO weapons and ammunition, it could inflict serious losses on the invader while liberating large amounts of Ukrainian territory, yet that didn’t happen. The offensive’s ending was just as mysterious as its kickoff, with Kyiv going silent about what was going on at the front. Nevertheless, it was evident by December that the operation had wound down without any significant gains. Kyiv admitted that it had liberated a dozen or so villages with a prewar population of 5,000. Operation STORM, this most certainly was not.

How many casualties the ZSU took for those modest gains can only be guessed at, since Kyiv keeps its losses secret, but numerous reports of whole battalions being gutted by trench-style attrition indicate that losses among the ZSU’s top brigades were steep. Losses of NATO-gifted armor and artillery were also serious, while the operation stripped Kyiv’s shell reserves almost bare. By the end of 2023, Ukraine was nearly out of artillery rounds and NATO’s own 155mm reserves have been seriously depleted by this war.

The great mystery here is why Kyiv allowed this blood-drenched operation to proceed into the autumn at all, when it was abundantly clear that the ZSU lacked the combat power to achieve major breakthroughs. How many lives were thrown away after any hopes of victory dissipated cannot be answered at present, but this surely has something to do with reports of low morale in tired Ukrainian ranks, even in some of the best units. Russian casualties were likely as high as Ukraine’s, given the harsh nature of attritional warfare plus Moscow’s lack of concern for its soldiers, but given Russia’s much bigger population, that fearsome equation cannot favor Ukraine in the long run.

Kyiv’s 2023 “counteroffensive” offers a cautionary tale about the perils of overpromising then underdelivering. Ukraine has proffered the expected explanations for failure: We underestimated Russian strength, defense in depth is difficult and costly to overcome, but above all, NATO let us down. In Kyiv’s telling, if only NATO, especially the U.S., had given Ukraine considerably more weapons and munitions, Russia would have been defeated. The stark truth is that European NATO broadly lacks much more to give Ukraine, while even the Pentagon is concerned that its readiness for an increasingly likely war with China has been hampered by gifting Ukraine so much ammunition and gear. Although President Biden has stated that America will support Ukraine for as long as it takes, it’s clear that many Americans no longer agree, including more than a few military leaders, privately, as they look across the Pacific with mounting worry.

There are remarkable parallels in this conflict with World War One, not just in the tactical realm – the nine-month bloodbath at Bakhmut looked a lot like Verdun writ small – but strategically too. This newsletter was the first to observe some remarkable resemblances between Ukraine’s war against Russia and Austria-Hungary’s war against Russia a little over a century ago, most of which took place in present-day Ukraine. Such similarities have only grown more noticeable over time, and since Austria-Hungary’s Eastern Front in WW1 was a costly rollercoaster affair, with some highs and many lows, that’s not good news for Kyiv.

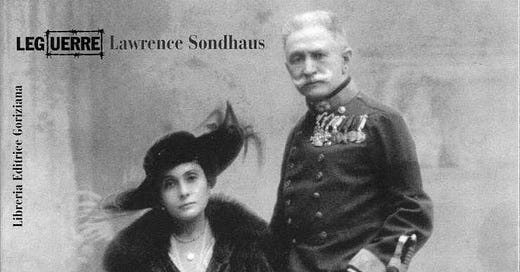

To illuminate the similarities, we need a quick run-through of how Vienna got mired in an attritional bloodbath with the Russians in the first place. Here we must turn to Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, Austria-Hungary’s top military man and General Staff chief from 1906 to 1917 (with a brief interruption in 1911-12). No person bears greater responsibility for Vienna’s defeat in WW1, and the subsequent disappearance of Austria-Hungary, than Conrad, who constitutes one of modern history’s stranger characters. Intelligent and driven, Conrad nevertheless displayed dubious judgement when he was most needed. His understanding of tactics was outdated even by 1900, while his grasp of strategy was remarkably weak. Neither was his selection of top generals to serve under him better than a mixed bag. Then there was his messy personal life. In the run-up to WW1, Conrad was focused more on his married mistress, a mother of six who was half his age, than war preparations. He battled serious depression over their melodramatic relationship, and the widower Conrad somehow got it in his head that his beloved Gina would leave her husband for him if only he could prove himself a successful war leader.

There is no doubt that Conrad’s booty-blindness, as we might put it today, was a factor in his madcap decision-making at the beginning of WW1. Surmising correctly that Belgrade was behind the Sarajevo assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Conrad demanded war against Serbia – he had done this repeatedly since 1908, now was his chance – and he got it. He displayed little concern that attacking Serbia was certain to provoke Russia, their Orthodox Slav big brother, to attack Austria-Hungary. Conrad was aware that his army was too small and too poorly equipped to manage a two-front war, but he went for it anyway.

In the late summer of 1914, Conrad’s army embarrassingly failed to subdue Serbia while it got crushed by the Russians in Galicia, today’s Western Ukraine, losing 400,000 men dead, wounded, or captured in just three weeks, a horrific blow from which Vienna’s military never recovered. Conrad kept his job and insisted that the Russians had to be stopped before they broke through into Hungary. That resulted in the Carpathian campaign during the first four months of 1915, a mostly forgotten catastrophe which unfolded in today’s westernmost Ukraine, witnessing Austro-Hungarian and Russian troops battling each other in frozen mountain passes. Conrad stopped the Russians but at the cost of 800,000 troops as whole battalions disappeared in snowdrifts. The Russians absorbed even more casualties, a million men, yet somehow both armies struggled on. (One of the oddities here is that twenty-first century states are much less successful at harnessing their manpower than they were a century-plus ago: the Russian Federation has almost as many people as the whole Russian Empire did in 1914, and Tsar Nicholas II mobilized millions of men into his army, but Putin can’t come up with a million troops; similarly, Ukraine is having difficulty staffing even a dozen new brigades – to a historian this is puzzling.)

What saved Conrad from total defeat in the Carpathians was the Germans. Relations between Berlin and Vienna were never easy, and they worsened as Austria-Hungary grew dependent on German munitions and sometimes troops to survive on the Eastern Front. Ostensibly allies, the Prussians and the Austrians rarely saw military affairs eye-to-eye. The Austrians considered their ally to be tactless and demanding, while the Prussians viewed the insincere Austrians as inefficient and bumbling (to be fair, Prussian officers viewed everybody but themselves like this). A popular wartime wag had it that the situation in Berlin was serious but not desperate, while in Vienna it was desperate but not serious.

Berlin was irritated by Austro-Hungarian dependency, yet they had no choice: if Vienna was defeated, Germany’s defeat would not come far behind (this was precisely what happened in the autumn of 1918). Therefore, the Prussians gritted teeth and gave their needy ally the shells and war materiel they needed to survive. Conrad quietly loathed the Prussians, referring to them as “our secret enemies” to his staff officers, while resenting his mounting dependence on Berlin.

Assessing that Austro-Hungarian forces in the Carpathians were on the cusp of collapse, Berlin loaned several of their best divisions plus ample stocks of heavy artillery and ammunition to Conrad, striking the tired Russians in early May 1915 near Cracow. Guided by excellent intelligence, the Prussians tore a massive hole in the Russian lines which quickly turned into a rout for the invader. By the time the front stabilized at the end of the summer, the Russians had retreated over 200 miles while losing more than a million men, half of them taken prisoner. This was an epic defeat, remembered by history as the Gorlice-Tarnów Offensive, which saved Austria-Hungary from the Russian bear. Nearly all the territory which Vienna had lost a year before in Galicia was liberated and the tide on the Eastern Front was turned decisively.

At this point, a sensible commander would have focused on rebuilding his damaged forces – in the first year of fighting, Austria-Hungary had lost roughly two million men – while training and equipping fresh divisions. Of course, that was not what Conrad did. Eager to prove his mettle while assuaging his vanity, Conrad ordered a major offensive against the Russians, whom he assessed were breaking down after the summer’s defeats. Austro-Hungarian intelligence assessed matters differently, but Conrad ignored that, just as he averted his eyes from strategic realities a year before. Importantly, Conrad eschewed Prussian assistance: he wanted this to be his victory alone. Berlin was skeptical but unable to restrain Conrad. The grand offensive was hyped by Viennese propaganda outlets, billed as payback for the initial defeat in Galicia one year earlier. This victory would restore the honor of the Habsburg dynasty and Conrad himself.

It never happened. Launched as summer’s end approached, the offensive hurled some 40 Austro-Hungarian divisions, most of the Habsburg Army, at the enemy in what is today western Ukraine, but no major breakthroughs materialized. Conrad’s forces lacked numerical superiority over the defenders and without Prussian heavy artillery backing them up, his regiments became mired in bloody slogs in forests and swamps. Casualties mounted as Austro-Hungarian forces nibbled away at Russian defenses, without serious impact. Nevertheless, Conrad kept the offensive going, unconcerned about casualties. As weeks dragged on without any breakthroughs, Conrad insisted the offensive was working, lying to the Austro-Hungarian public. His own staff officers grew concerned with the failure, referring to the offensive among themselves as Conrad’s Herbstsau – a hunting term meaning “autumn swinery” but more accurately rendered as “fall fuck-up.”

Frederick the Great once said that it wasn’t enough to beat the Russians, you had to beat them dead, a lesson that Conrad learned painfully in the autumn of 1915. In mid-October he called off his abortive offensive, having achieved no real gains, while losing over 200,000 men, including an alarming number of “missing” i.e. prisoners. In the last weeks of the hopeless offensive, exhausted Habsburg troops were surrendering to the Russians in droves. As was standard in such attritional fights, Russian losses proved as high as Conrad’s, but the enemy still possessed vast manpower reserves to tap into, while Vienna did not.

Privately, the Prussians fretted that Conrad was inept yet overconfident, a deadly combination, while his army was alarmingly brittle. As was his custom, Conrad covered up the disaster, while insisting it was somehow Berlin’s fault. The offensive makes a modest appearance in the Austro-Hungarian official history of the war, authored in the 1930s by Conrad protégés, which bills it as the “Rovno campaign.” You have to read between the lines to realize this was a needless disaster. As a result, Conrad’s Herbstau all but disappeared from memory, and even many WW1 historians have never heard of it. Sometimes cover-ups work.

Fortunately for Conrad and his tired army, the Eastern Front was rather quiet during the winter of 1916. The Austro-Hungarians and Russians were bloodied and exhausted alike, so they spent the winter hunkered down, rebuilding strength. Indeed, by the spring of 1916, Conrad and his generals were remarkably confident of their position in the east. All along the extended front, Austro-Hungarian forces occupied impressive entrenchments backed by ample artillery, while manpower losses had been made good with callups of middle-aged men and teenagers.

Therefore, intelligence warnings in the late spring that Russian forces were plainly planning a major offensive were dismissed by Conrad and his generals as a feint. Besides, they assessed, the Russians were tired and therefore incapable of breaching stout Austro-Hungarian defenses. They guessed wrong – badly wrong. To make matters worse, Conrad had shipped several of his best divisions to the Italian Front to launch an offensive (it failed) on the Asiago plateau, Conrad’s pet project (he disliked Russians and loathed Serbs, but Conrad positively hated Italians).

When the Russians struck in early June, Austro-Hungarian forces on the Eastern Front got steamrollered like never before. Aleksei Brusilov, the tsar’s best general, launched his battle-ready Southwestern Front at the enemy on what Russians would remember as the Glorious Fourth of June, their greatest success in the war. Although Brusilov possessed minimal manpower advantage over the Austro-Hungarians, he shattered their entrenchments and their artillery with well-coordinated blows by his own heavy artillery, backed by large shell reserves, while pinpointing infantry attacks along narrow corridors to overwhelm the enemy.

It worked perfectly. Stunned Austro-Hungarian troops reeled from unprecedented shelling, while whole regiments got trapped in their entrenchments as Brusilov’s surging units advanced past them. Within days, Conrad’s Eastern Front was falling apart. His troops’ morale collapsed, battalions were surrendering to the Russians en masse, while others were retreating as fast as they could run. Reluctantly Berlin dispatched whatever it could to save Conrad yet again. It was only a few divisions and some heavy artillery – Brusilov launched his great offensive to help his French ally, who was bleeding out at Verdun that summer, so Berlin had scant reserves to spare – but it was enough to prevent complete Austro-Hungarian collapse, barely.

The fighting raged through the summer and casualties mounted. By the end of Brusilov’s offensive, his own losses were as steep as Conrad’s, but Russia had broken the back of the Austro-Hungarian Eastern Front. Conrad lost some 800,000 men, half of them prisoners, casualties which Vienna could no longer make good. Moreover, the confidence of his army was shattered, never to recover against the Russians. Prussian assistance was needed to stave off full Austro-Hungarian collapse as Berlin added their battalions to Conrad’s divisions as “stiffeners,” while at every level of Austro-Hungarian command in the east, Prussian staff officers took charge of operations, leaving their allies a fig leaf of accountability to salvage a smidge of pride. Henceforth, Conrad’s Eastern Front was no longer really his own, while Berlin continued to dispatch troops, weapons, and munitions to their ailing ally to keep them in the war. It worked for two more years.

Luckily for Conrad, Russia fell apart in 1917 amid domestic tumult and revolution. In early 1918, the new Bolshevik regime took Russia out of the war, leaving the Central Powers with an unexpected default victory in the east. Perhaps Ukraine will prove equally lucky, and the Putin regime will collapse by itself, under wartime pressures. Russia frequently turns out to be more brittle than it seems from a distance. However, if there is no palace coup or similar in the Kremlin, we should expect a major offensive from Moscow sometime in the spring.

Will it work? Can Russia muster a serious strategic offensive against Ukraine – or will it peter out painfully like Kyiv’s vaunted offensive just did? Has technology made the defense uniquely strong, rendering big offensives costly and difficult, and sometimes simply impossible – just as happened in World War One, until armies gradually developed new tactics to match the emerging technology?

The good news is that the battlefield offers no cover anymore. Thanks to cheap and ubiquitous drones on the battlefield, “the other side of the hill” is visible as never before. Ukrainian intelligence will likely detect any major Russian offensive as it develops, and if Kyiv misses it, NATO intelligence will not. Putin’s corrupt and stagnating Russia seems unlikely to produce another talent like Brusilov, but the bad news is that any significant Russian attacks might deliver harsher blows than Ukraine’s depleted military can withstand. In the event of any Ukraine battlefield collapse, NATO troops – not just weapons and munitions – will be needed to prevent Kyiv’s strategic defeat. However, any such NATO intervention in the conflict, in the manner of Berlin saving Conrad several times, will result in World War Three between nuclear powers.

How likely is that? In such cases, I recommend heeding the wisdom of the venerable Zen Master.

*Kyiv labels all its major attacks on Russian forces as “counteroffensives” to remind everyone that Moscow invaded their country; they are not counteroffensives in the definitional sense.

Postscript: Conrad was terrible at waging war, but he got the girl anyway. Gina consented to leave her husband, joining Conrad at his palatial headquarters safely behind the front, where he engaged in more afternoon delight than his concerned staff officers considered appropriate as his army was dying. Scandal at court followed but Conrad cared more about Gina than anything else. They eventually married and settled into domestic bliss as the empire collapsed around them. After the war, Conrad published his detailed memoirs, which blamed everyone but himself for defeat, the Prussians especially. After Conrad’s death in 1925, when he was bizarrely heralded by the Austrian public as a genius at war, Gina published a tawdry memoir of their affair, including his pathetically anguished love letters, begging her to leave her husband. It became a bestseller.

A happy couple in unhappy times #LoveWins